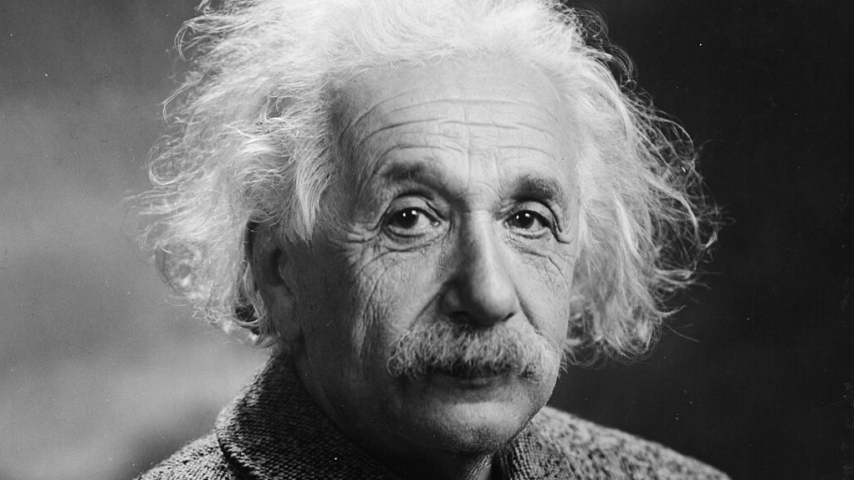

Photo credits: Wikipedia. Albert Einstein

Secrets of Success, Love, and Life: The Legacy of the World’s Visionaries. A recurring Monaco Voice column exploring the lives, achievements, and philosophies of the world’s most influential visionaries, uncovering the secrets behind their success and enduring legacies curated by actress Vladyslava Garkusha.

Before Albert Einstein was the world’s most beloved physicist - he was a quiet man with a violin, a stack of patent applications, and a universe to reinvent. That he did so from a desk in Bern, without academic title or laboratory access, remains one of the more exquisite subversions in modern intellectual history.

In 1905, at just 26, Einstein published four papers that would alter the fabric of physics. Time, it turned out, wasn’t absolute. Mass and energy were two sides of the same cosmic coin. And light had a few more tricks up its sleeve than Newton had guessed. Today, we call that year his Annus Mirabilis. Did Einstein call 1905 miraculous - or just a productive season? Or perhaps a bit of both?

He worked days at the Swiss Patent Office, rejecting dubious inventions with clinical detachment, and wrote physics by night - disrupting the very assumptions underpinning classical mechanics. His equation, E = mc², elegantly minimal and maddeningly profound, emerged from this period. And no, he was not yet a professor.

The Love Lab

Einstein’s scientific method was precise. His personal life? Considerably less so.

He met Mileva Marić at the Zurich Polytechnic. She was a Serbian physics student, one of the few women in Europe pursuing the subject seriously. Their courtship was fueled by equations, ideals, and shared resistance to the polite expectations of their time. She was intelligent, sharp-witted, and, like Einstein, more interested in ideas than conventions.

Photo credits: Wikipedia. Albert Einstein and Mileva Marić Einstein, 1912

Between 1899 and 1903, Einstein and Marić exchanged dozens of letters - many of which survive today, published in The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein. These letters reflect a passionate, intellectually infused relationship: Einstein often shared ideas, discussed books, referenced physics lectures, and expressed love with youthful intensity and the occasional equation. He called her “Dollie,” signed letters “your Albert,” and occasionally mentioned his scientific progress in real time. The infamous line appears in a March 27, 1901 letter:

“How happy and proud I will be when the two of us together will have brought our work on relative motion to a victorious conclusion!”

Her own academic career stalled - she failed her final exams twice and did not receive her diploma. They married in 1903, had two sons, and grew steadily apart. The strain of domestic life, scientific ambition, and emotional detachment turned love into something more contractual. By 1914, Einstein offered a list of demands for their continued cohabitation. (“You will stop talking to me if I request it,” was one. Romance, it seems, had left the building.) She left. They divorced in 1919.

Less than a year after his divorce from Mileva, Einstein married Elsa Löwenthal in 1919. Elsa, a cousin on both his mother’s and father’s side, had been a close companion for many years. She had been married once before, but her previous marriage had ended in tragedy with the death of her first husband. Elsa brought a sense of stability and support to Einstein’s life at a time when his fame was reaching new heights. Their marriage, though unconventional, provided Einstein with emotional support. Elsa managed much of Einstein’s day-to-day affairs, allowing him to focus on his scientific work. She was a constant presence in his life, accompanying him on lecture tours and acting as a buffer between him and the public. Elsa was not a fellow scientist, but she understood Einstein's work and its demands on his time. They remained married until her death in 1936.

Photo credits: Mètode. Albert Einstein with his second wife, Elsa, in 1921 in Washington DC

From Relativity to Statesmanship

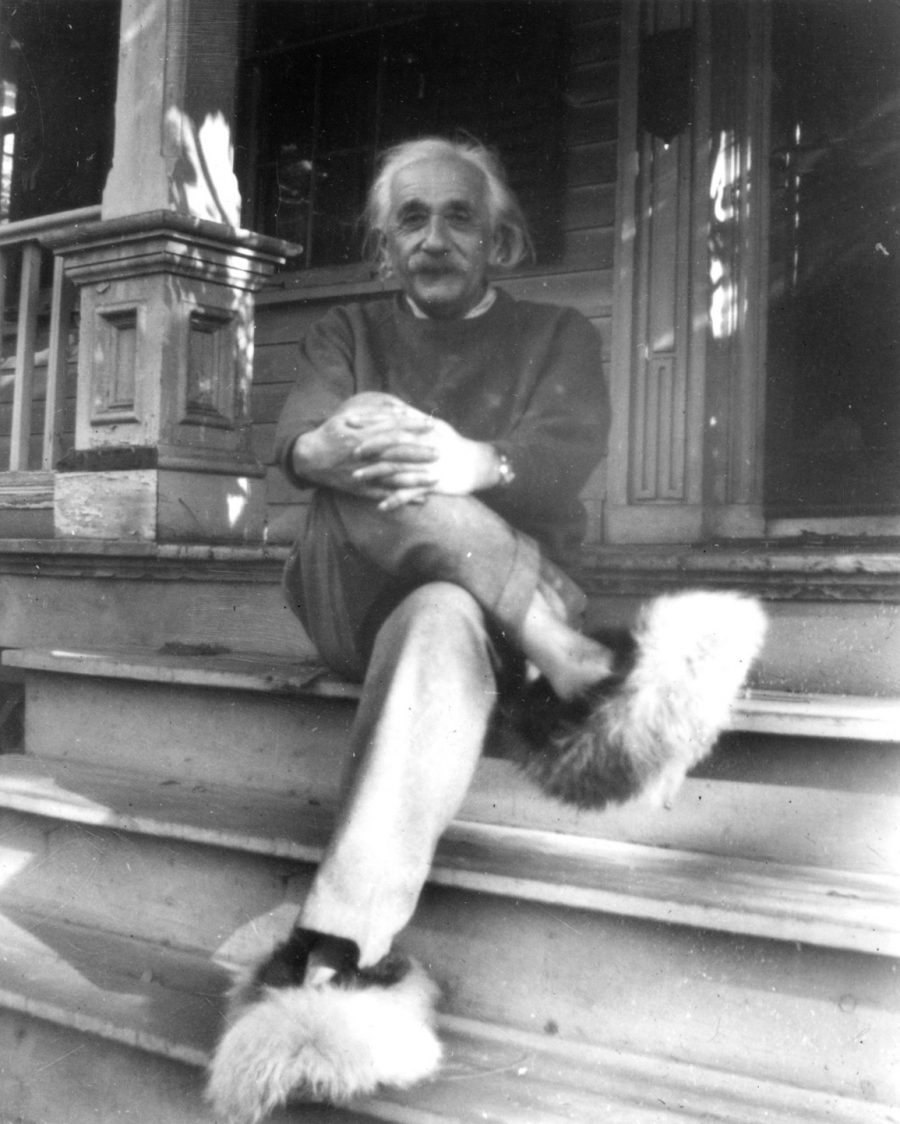

By the 1920s, Einstein was no longer a physicist. He lectured in packed halls in Japan, wandered Hollywood sets with Charlie Chaplin, and called nationalism “an infantile disease”. In 1933, as the Nazi regime consolidated power, Einstein formally renounced his German citizenship and settled at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study. He would remain there for the rest of his life.

It was in Princeton that Einstein transitioned to statesman. He denounced fascism, racial segregation, and anti-Semitism. He joined the NAACP, praised civil rights leaders, and decried the hypocrisy of a nation battling Hitler abroad while enforcing Jim Crow at home. Racism, he wrote, was a “disease of white people.”

Though he abhorred violence, Einstein signed a letter in 1939 to President Franklin D. Roosevelt - co-written with physicist Leo Szilard - warning of Nazi Germany’s interest in nuclear weapons. That letter led to the formation of the Manhattan Project, though Einstein himself played no role in the bomb’s creation.

He later called the letter his “one great mistake.”

In 1946, he publicly condemned the use of nuclear weapons and became a supporter of the United Nations as a way to foster international cooperation and prevent future wars.

The Fluidity of Time and Space

Einstein’s theory of relativity reshaped our understanding of the universe. Time, space, and gravity are no longer fixed; they are interconnected and dynamic. Time itself slows down for objects moving at high speeds, a phenomenon called time dilation. Space is also bendable, with massive objects warping the fabric of spacetime, creating what we feel as gravity.

Einstein’s equation, E = mc², showed that mass and energy are interchangeable, revealing the profound connection between the two. In essence, we now see the universe as a fluid, ever-changing system, where time, space, and energy shape each other in ways that continually redefine reality.

Trusting the Unseen

Einstein famously said, “Imagination is more important than knowledge.” His life suggests that success, love, and legacy are not linear formulas. They are, like the cosmos he reshaped, full of paradox and movement.

Photo credits: The Historical Society of Princeton. Albert Einstein sits on the porch of his home at 112 Mercer Street

He was difficult, brilliant, flawed, romantic, deeply principled - and endlessly curious. It wasn’t just that he imagined the universe differently. It’s that he had the courage to insist he might be right.