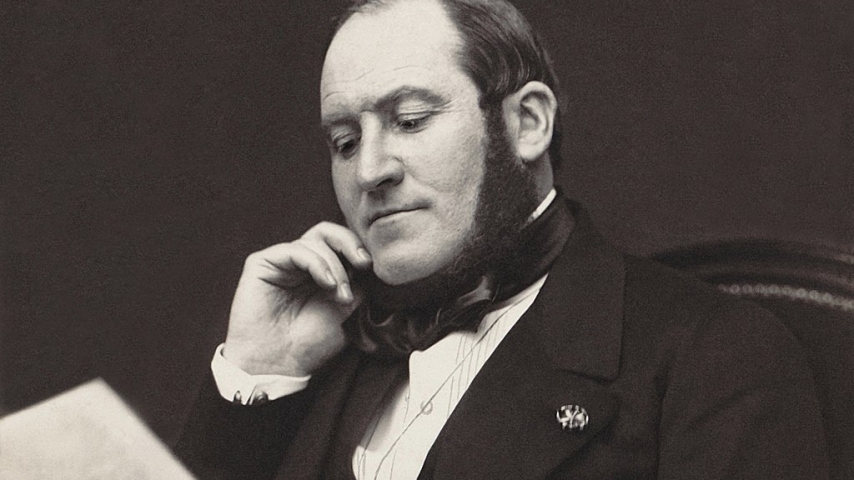

Photo credits: Wikipedia. Georges-Eugène Haussmann.

Secrets of Success, Love, and Life: The Legacy of the World’s Visionaries. A recurring Monaco Voice column exploring the lives, achievements, and philosophies of the world’s most influential visionaries, uncovering the secrets behind their success and enduring legacies curated by actress Vladyslava Garkusha.

By the mid-19th century, Paris had a problem. Actually, it had several: overcrowded medieval alleys, poor sanitation, choking traffic, and a growing reputation as a hotbed for political uprisings. Enter Georges-Eugène Haussmann, a relatively obscure bureaucrat who would, in less than two decades, redraw the city - and its future - one boulevard at a time.

Appointed by Napoleon III in 1853 as Prefect of the Seine, Haussmann’s task was daunting: modernize a chaotic, pre-industrial Paris into a capital worthy of empire. His approach was neither tentative nor subtle. Entire neighborhoods were razed. Roughly 20,000 buildings were demolished. Long, straight boulevards were carved through ancient quarters. Critics called it brutal. Haussmann called it necessary.

But to understand how he got there, it helps to go back to the beginning.

From Paris, with Plans

Georges-Eugène Haussmann was born on March 27, 1809, at 55 Rue du Faubourg-du-Roule in Paris. His family background was part revolutionary, part imperial. His paternal grandfather was a deputy during the French Revolution; his maternal grandfather, a general ennobled by Napoleon I. Haussmann was raised partly in Chaville and returned to Paris to attend Collège Henri-IV, followed by Lycée Condorcet. He studied law and music, and earned his law degree (and later, a doctorate) by 1831.

Haussmann entered the civil service early and climbed steadily: from sub-prefect in Nérac to prefect in Bordeaux. His reputation was one of quiet efficiency. When Napoleon III needed someone to carry out an urban revolution in Paris, he didn’t look for a visionary architect. He hired a functionary who could execute.

The Blueprint of Success

Haussmann was not an architect by training, but his administrative precision rivaled that of any seasoned urban planner. With a combination of imperial mandate and civil servant rigor, he oversaw a sweeping transformation: an overhauled sewer system, expanded aqueducts, gas-lit streets, new parks, and a uniform building code that defined the Haussmannian aesthetic - five-story stone façades with iron balconies and strict height regulations.

Some saw the wide boulevards as a clever way to deploy troops quickly and prevent barricades during uprisings. Others, especially developers, saw a real estate windfall. Haussmann, for his part, insisted it was about health, order, and modernity. All three viewpoints hold up under scrutiny.

Photo credits: Architectural Digest.

The Green Revolution, Paris-Style

Haussmann’s Paris wasn’t just steel and stone. It was also green. Under his directive, more than 2,000 hectares of new parks and gardens were added, including the Bois de Boulogne in the west and Bois de Vincennes in the east. Haussmann prioritized the creation of parks and green spaces so that more Parisians could have easier access to nature and fresh air.

Secrets of Love

Haussmann wasn’t a romantic in the public sense - he wrote no great love letters, composed no flowery dedications. But he married young and stayed committed. In October 1838, he married Octavie de Laharpe, a Protestant like himself. They had two daughters, Marie-Henriette and Valentine, and remained together for more than five decades until their deaths. Those closest to him described him as private, sometimes gruff, but deeply loyal - qualities that extended, one could argue, to both his family and his unwavering vision for Paris.

His eternal love story, perhaps, was also with the city itself. He didn’t just improve Paris; he imposed a lasting form on it. A rationalist to the core, his passion showed up in street widths and drainage gradients.

The Backlash and the Bottom Line

Of course, all this ambition came at a price -not just financial (the costs nearly bankrupted Paris), but social. Entire communities were displaced. Tens of thousands of working-class residents were pushed to the city’s outer edges. Critics argued the redesign served bourgeois aesthetics and political control more than the public good.

Photo credits: Raphael Metivet Photographer Instagram.

By 1870, with Napoleon III’s fall and the Second Empire in retreat, Haussmann was dismissed. He left office amid political fatigue, financial controversy, and rising public anger. But he also left behind a radically transformed city that, for better or worse, still bears his name.

He died on January 11, 1891, just 18 days after his wife Octavie. They are buried together in Montmartre Cemetery.

Legacy by Precision

Walk through Paris today and you’ll find his imprint on nearly every corner. The grand boulevards, the rhythmic façades, the sweeping vistas and leafy promenades - all of it is Haussmann’s handiwork. He didn’t just modernize a city; he manufactured its myth.

In the end, Georges-Eugène Haussmann didn’t just pave the streets of Paris - he reimagined what a modern city could look like. Efficient. Elegant. Romantic. And, yes, a little authoritarian.